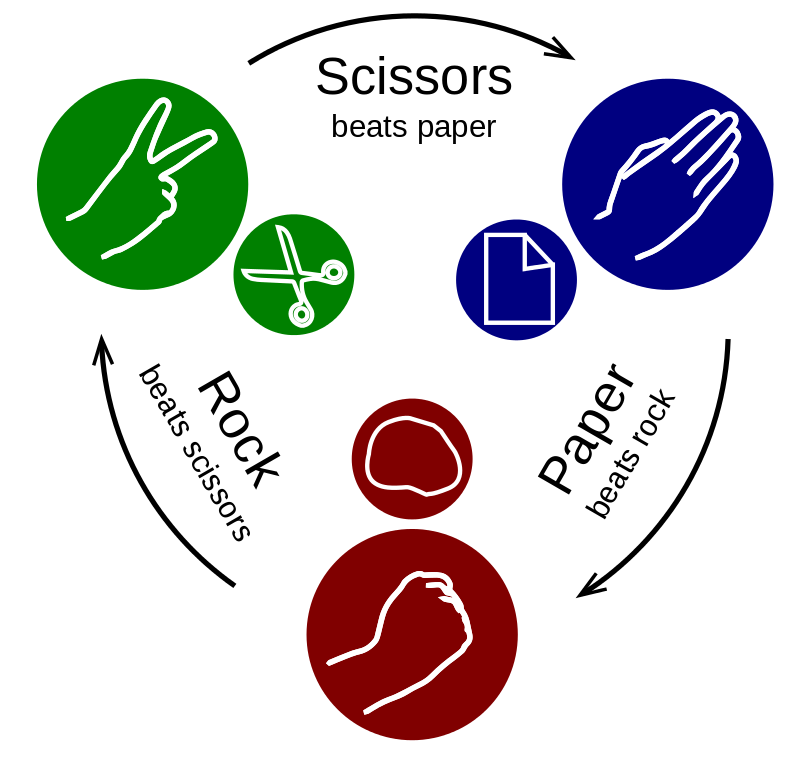

So far, this blog has mostly focused on video games, but they are not the only type of game that can be analyzed using flow theory. Any activity can induce flow, but video games just happen to be very well-suited for it. This week we will look at a non-digital game that has been around for thousands of years: Rock-Paper-Scissors.

Challenge and Skill. Rock-Paper-Scissors is a PVP game, so a large part of the challenge depends on the skill of the opponent. However, it is also largely random, since neither player typically has any clue as to what their opponent will play. Challenge and skill come into play only at the absolute highest levels of play, where reading and conditioning the opponent’s moves become the only way to gain an edge. But for the average player, Rock-Paper-Scissors is a game of complete chance with no opportunities for skill expression and therefore no varying degrees of challenge, since challenge is based on the skill of the opponent.

Goals. Rock-Paper-Scissors does allow for very proximal goal-setting, since each game takes only a couple of seconds. The player will always know what their current objective is. This is the gold standard for flow, when the player never questions what they should be doing. In this area, Rock-Paper-Scissors benefits from being so simple. Modern games often have far more complex rules and objectives, so it is important for them to be as clear as possible regarding what the player should be doing at any given moment.

Feedback. For a non-digital game, Rock-Paper-Scissors does a good job at providing immediate feedback to players. However, this is again largely due to its simplicity. The only feedback necessary is which sign each player selected and, by extension, which player won, if any. So long as neither player tries to form some kind of hybrid, in-between shape with their hand for the purpose of being able to argue that they chose either of two signs, the results should be fairly obvious. The signs are distinct enough that both players will know what the other selected as soon as they are played. The feedback that Rock-Paper-Scissors does provide, it provides very well. However, it does not provide feedback beyond this. If Rock-Paper-Scissors were created today, it would likely have things like a scoreboard to keep track of series longer than one game as well as a statistics page for each player to give feedback on recent and lifetime match history and sign preference. But for the purpose of providing feedback on single games, Rock-Paper-Scissors does a very good job.

Improvements. Without changing the fundamentals of what makes Rock-Paper-Scissors what it is, challenge and skill could not be improved very much. If it were a video game, a matchmaking system could be implemented to pair players of equal skill levels. Player profiles and stats pages could also be created to keep track of any preferences players have or any recent habits they have formed. This would help not only plan for certain opponents, but it would also help players notice their own habits and mix them up.

Conclusion. Rock-Paper-Scissors is a very simple game, making it very easy to pick up and very difficult to express skill in. This often leaves it at low-challenge and low-skill, making it poorly suited for flow experiences. However, this simplicity means that player goals are always clear, and feedback arrives immediately. There is never a question of what the player should be doing, and there should never be a question of the results of a game. If Rock-Paper-Scissors allowed for more skill expression and challenge, it would be a great game for inducing flow.

Huh, that’s an interesting concept! As you said, the goals and feedback could not really be any clearer/more immediate, and the challenge and skill are (for “normal players”) practically non-existent. So, theoretically, 50 % of the criteria of inducing flow is met perfectly, and the other 50 % cannot be met.

From my own experience, that sums it up pretty good. If you play to, let’s say, decide who gets the last slice of pizza, then there will be no flow. In order to induce flow, we’d have to find a way to increase the challenge, so that actual skill is required.

And there is a way! Increase the number of rounds played (30+ rounds), require the players to keep track of them, and increase the overall tempo of the game. Each player gets a sheet of paper and a pencil (or something to make notes). Each round is played the normal way (1,2,3,reveal), and there’s only another moment to realise the outcome. The player who won marks is on his sheet and announces the round counter. Then, without pause, the whole cycle continues. For each mistake, of course, one victory gets deducted.

The challenge now comes from the split-second decisions the players have to make, as well as keeping track of their victories and the round number. I borrowed this kind of “mechanic” from reaction card games, and it seems to work perfectly. There is no time to think calmly about what you or your opponent have done and might do, but you have to analyze the game in a matter of moments.

The players skills cannot really be “overburdened”, because you still can just throw random signs, if you can’t keep up with the counting. But knowing that the opponent reacts instinctively you can try to identify patterns and try to react to them properly.

I have played many games in this style and I have to say, you really completely blend out your surroundings and only exist within the game. That’s flow if I’ve ever seen it…

LikeLike

And that’s exactly what makes virtual games particularly good at getting players into the state of flow. They can be designed in such a way that those additional rules you mentioned are just part of the game. And rather than relying on potential human error for the countdown and tracking of points, a virtual countdown could appear and a scoreboard could automatically keep track of things. This would speed up the game even more, making it that much more challenging and allowing an attentive player to capitalize on their opponent’s habits. I’ve found that perhaps the most important part of flow is to always be doing something and to always know what it is you’re doing.

LikeLike

“Always be doing something and always know what it is you’re doing”. Yes, I think that sums it up pretty nicely 🙂

LikeLike